Author: Jaime Derringer (she/they), Associate Professor of Psychology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

This repository contains open educational resources (OER) for PSYC 408 Human Behavior Genetics.

The last major update of content was for the Fall 2023 semester; it is currently being revised for the Fall 2025 semester.

- Syllabus

- Ethics Statement

- A Note on Pedagogy

- Course Structure

- Integry and “AI” Policy

- Accessing Course Readings

- Frequently Used & Additional Resources

- Part I: Methods and Concepts (weeks 1-5)

- What We Know and What We Don’t

- We’ve Been Wrong Before

- Finding and Reading Behavior Genetics Research

- Height: A Model Phenotype

- Ancestry: What It Is and Isn’t

- Part II: Phenotypes and Processes (weeks 6-10)

- Schizophrenia: Psychometrics + Biometrics

- Autism: Heterogeneity and Disability Perspectives

- Causal Reasoning in Substance Use and Aggression

- Internaliing, Stress, and Gene-Environment Interaction

- Cognitive Ability, Educational Attainment, and Gene-Environment Correlation

- Part III: Applications and Ethics (weeks 11-15)

- Science Communication

- Data Privacy, Law Enforcement, and Discrimination

- Genetic Engineering

- Personalized Medicine, Personalized Education, and Direct-To-Consumer Tests

- GATTACA, and Genetics as a Social Construct

Syllabus

The aim of this course is to provide students with a clearer understanding of the contribution that genes make to individual differences in behavior. Students will be in a better position to evaluate evidence for and against genetic and environmental influences. They will also gain an appreciation of the interrelationships of biological and social causes of behavior and will gain a better understanding of influences that might affect themselves and others.

In this course you will:

- Understand how the basic principles of genetics can be used in the study of behavior,

- Evaluate the extent to which human individual differences are influenced by genes,

- Consider the implications of genetic knowledge in psychology.

There are no prerequisites for Psyc 408. If you think the material sounds interesting, this class is for you!

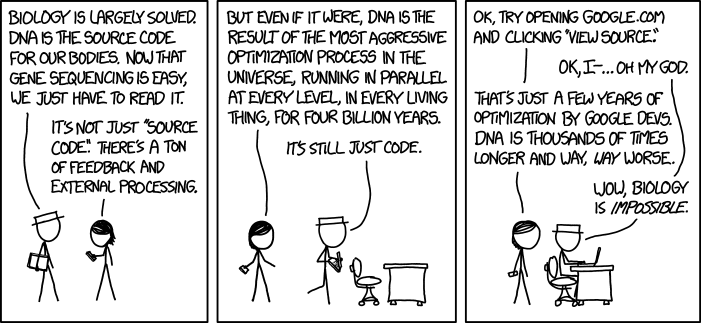

xkcd, “DNA”

xkcd, “DNA”

Ethics Statement

The history of behavior genetics is inextricably linked with eugenics and racism.

We will discuss the historical and current ways in which behavior genetics has been used to support white supremacy, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and ableism.

The use of behavior genetics research and principles to support racism and other forms of discrimination is based on (often willful) misinterpretation of the underlying statistical models on which the science relies.

There are reasonable questions to be asked about whether it is possible to conduct behavior genetics research without doing harm to marginalized people.

One goal of this course is to understand the forms of knowledge production that are used within behavior genetics, interrogate the limits of that knowledge, and consider how behavior genetics has been/is/will be used (and misused) to impact the lives of real people.

A Note on Pedagogy

The course that follows these materials, as I teach it, is a 15-week advanced undergraduate/introductory graduate course focused on developing core competencies that allow for the critical evaluation of current and future knowledge. Because genetics - especially as related to complex behaviors and experiences - is a constantly developing field, and because you never know what you might need to learn about in the future, I focus skill development on accessing, reading, evaluating, and synthesizing the primary research literature. There are no exams in my course, and the major grade/product is a term paper on any topic of the students’ choosing (along with an accompanying piece of public-oriented science communication). Even in a large lecture course, I am able to manage individual development of highly specialized/selected areas of expertise by following a heavily scaffolded process (developed over a decade of teaching and growing this class) that helps students learn to learn.

Every instructor or textbook author necessarily makes decisions about what content to include, to focus on, to elevate or gloss over, and I am no different. There is no such thing as a neutral presentaion of any topic, much less one that has such profound and personal implications for individuals and society. For this reason, the material is not written as if by a neutral third party - I very intentionally present information from my first-person perspective, as both an expert in the field and as a whole human being.

This course is designed differently than the typical human behavior genetics course. The focus is less on preparing STEM-focused students to be academic or industry researchers (although many of my students certainly go that way) and more on preparing a diverse range of undergrads and graduate students to be consumers, caregivers, and citizens in a world where genetics is increasingly marketed as a way to make critically important decisions, both personally and as a society.

If you are looking for material that takes a more standard approach to an introduction to human behavior genetics, I recommend Scott Stoltenberg’s Foundations of Behavior Genetics textbook and/or Matt McGue’s Introduction to Behavioral Genetics course on Coursera.

Course Structure

Consistent with an expectation that a course takes about 3 times the number of credits in hours per week, as a 3-credit course (for undergrads), plan to spend an average of 9 hours per week working on this course. Points earned for weekly participation activities and larger course project assignments are scaled such that each point is expected to take about 1 hour of effort, including time to prepare (e.g. read, think) and complete (e.g. write, edit) the task.

Grades are based on the total number of points earned by the end of the semester. Points come from weekly activities (up to five points per week for 15 weeks) and a course project (including six assignments leading up to a term paper, totaling up to 60 points). There are potentially 135 points to be earned throughout the semester.

| Points | Letter Grade |

|---|---|

| 120 + | A |

| 105 - 119.999 | B |

| 90 - 104.999 | C |

| 75 - 89.999 | D |

| < 75 | F |

There are no +s or -s, only letter grades.

You may notice that the table for converting points into final grades doesn’t quite scale at 10% increments (eg. 90% of 135 is 122.5, but you only need 120 points to earn an A). The extra cushioning on each letter grade is intended to serve as buffer for flexibility for absences or missed assignments.

Activities are scaled so that 1 activity = about 1 hour of effort = 1 point. You can earn up to five points per week from activities. Every week there will be more than five options for activities available; you are welcome to choose-your-own-adventure in terms of which activities you complete. The list of activities available each week is contained as the ‘module’ for that week. You are expected to at least skim everything early in each week to (1) decide which activities you’re going to do and (2) quickly be able to reference any particular section of readings that come up for discussion in class that week.

Weekly activities are due by Friday 5 pm that week. Late weekly activities may be submitted by Monday 5 pm for 80% credit.

Each class attended earns 1 activity point. Lectures and discussions will be generally structured around that week’s readings. Class attendance points can’t be made up or submitted late, but there will be at least five asynchonous activity options each week, so even if you are unable to attend class you can still earn all of your weekly points.

Outside of class, the most common weekly activity will be annotating/virtually discussing journal articles in Perusall. Perusall applies automatic scoring based on an algorithm that I define; usually, about 4 high-quality comments or replies on an article will earn a point.

Throughout the semester, you will develop a Course Project about a topic related to human behavior genetics that is of interest to you, with the goals of identifying, understanding, and synthesizing recent and historic scholarly sources; developing expertise in a specific topic of interest; and communicating knowledge to a general audience. The course project includes six major assignments up to and including the final paper:

- Week 8: Ten Scholarly Source Summaries (15 points

- Week 11: Draft Paper (10 points)

- Week 12: Draft Popular Source (5 points)

- Week 13: Paper Peer Reviews (15 points)

- Week 14: Final Popular Source (5 points)

- Finals Week: Final Paper (10 points)

Course Project assignments due during the semester are due by the Monday after the listed week by 5 pm. The Final Paper is due by 5 pm on the day our “Final Exam” would have been held based on the noncombined finals schedule. Late Course Project assignments lose 10% of their grade per day late.

Integrity and “AI” Policy

UIUC Student Code Academic Integrity Policy

Make good choices. You are ultimately responsible for the content of what you submit. The landscape of computer assistance for research and knowledge production is ever changing. A good guideline is that if you would be uncomfortable describing your process for producing work for this course (to me, to your parents, or announced on a roadside billboard), you should re-evaluate your approach. If you are in doubt, reach out to discuss options and approaches. I am a reasonable, practical person, and I can tell you from experience that the examples of (obviously) “AI” generated work that I have encountered have been terrible enough that they end up earning failing scores on their merits alone. We will work through some examples of how AI/large language models fail to reason competently in this area (true for most fields, once you get into advanced knowledge production and synthesis, as we do in college courses). If you would like to quickly see for yourself, try talking to any LLM about a topic you are very knowledgable about… it’ll say wrong things that sound good, except you know better. This is true for genetics as well (maybe even especially so, considering the amount of misinformation on the internet that these models have to draw from) - you will get a lot of confident nonsense that to an expert (like me) is obviously, hilariously, depressingly wrong.

Accessing Course Readings

PDFs of Course Readings will be posted on the course Canvas page.

If you are accessing readings from outside of the course, I’ve tried to mark articles that are freely available as (open access). For those that aren’t, many are old/popular enough that there are freely available PDFs floating around on the internet if you search for the article. If you have access to a University library system, most of these journals will likely be available online through your library.

When you pay to access a journal article, that money goes to the publisher, not to the authors or their institutions. Especially newer articles you can usually get by emailing the author (first, last, or corresponding) - we love to hear that someone wants to read our work! Services like Sci-Hub (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sci-Hub) bypass journal paywalls to provide free access.

During the first half of the course we will also be reading through Catherine Baker’s (2004) Behavioral Genetics: An Introduction to How Genes and Environments Interact Through Development to Shape Differences in Mood, Personality, and Intelligence, a product of a project conducted by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and The Hastings Center, which is available as an open access book.

Frequently Used & Additional Resources

- Lecture recordings (Fall 2023) on Illinois Media Space (requires Illinois login)

- Twenty themes in behavior genetics

- Identify scholarly versus popular sources

- Template to summarize a Scholarly Source that is reporting an Empirical analysis of data

- Template to summarize a Scholarly Source that is a Review of the existing literature

- Peer Review Template

- Essay Structure Template

- UIUC Department of Psychology list of internal and external Mental Health Resources

- UIUC Student Assistance Center for finding support for all kinds of issues

- UIUC Disability Resouces and Educational Services for accommodations

- UIUC DGS Student Success Toolkit for advice on note-taking, studying, and time management.

Schedule and Materials

Part I: Methods and Concepts

Week 1. What We Know and What We Don’t

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday, Friday

- Lecture Notes

- What is Behavior Genetics?

- 20 Themes in Behavior Genetics

- Baker, C. (2004). Introduction & Chapter One: What Is Behavioral Genetics? pp. vii-xi, 1-7. open access book

- Brandes, N., Weissbrod, O., & Linial, M. (2022). Open problems in human trait genetics. Genome Biology, 23(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-022-02697-9 (open access)

- Briley, D. A., Livengood, J., Derringer, J., Tucker-Drob, E. M., Fraley, R. C., & Roberts, B. W. (2019). Interpreting behavior genetic models: seven developmental processes to understand. Behavior Genetics, 49, 196-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-018-9939-6

- Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., Knopik, V. S., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2016). Top 10 replicated findings from behavioral genetics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615617439

Week 2. We’ve Been Wrong Before

- Lectures: Wednesday, Friday (No Class Monday, Labor Day)

- Lecture Notes

- Candidate Genes

- A Very Brief History of Eugenics

- Baker, C. (2004). Chapter Two: How Do Genes Work Within Their Environments? pp. 9-22. open access book

- Baker, C. (2004). Chapter Three: How Do Environments Impinge Upon Genes? pp. 25-37. visit open access book

- Allen, G. E. (1997). The social and economic origins of genetic determinism: a case history of the American Eugenics Movement, 1900–1940 and its lessons for today. Genetica, 99, 77-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02259511

- Duncan, L. E., Ostacher, M., & Ballon, J. (2019). How genome-wide association studies (GWAS) made traditional candidate gene studies obsolete. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(9), 1518-1523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0389-5

- Rembis, M. A. (2009). (Re) Defining disability in the ‘genetic age’: Behavioral genetics,‘new’ eugenics and the future of impairment. Disability & Society, 24(5), 585-597. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590903010941

- Activity: Eugenics Journal Response

Week 3. Finding and Reading Behavior Genetics Research

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday, Friday

- Lecture Notes

- Identify Scholarly Sources

- How To Read a Classical Twin Study

- How To Read a GWAS

- Baker, C. (2004). Chapter Four: How Is Genetic Research On Behavior Conducted? pp. 39-57. open access book

- Eftedal, N. H. (2020, June 17). Estimating heritability of psychological traits using the classical twin design; a gentle introduction to concepts and assumptions. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/g3f9c (open access)

- Tam, V., Patel, N., Turcotte, M., Bossé, Y., Paré, G., & Meyre, D. (2019). Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Genetics, 20(8), 467-484. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0127-1

- Activity: Estimate Heritability from Twin Data using Two Methods in R

- Activity: Interpret a Manhattan Plot

Week 4. Height: A Model Phenotype

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday

- Open Work Session: Friday

- Silventoinen, K., Sammalisto, S., Perola, M., Boomsma, D. I., Cornes, B. K., Davis, C., … & Kaprio, J. (2003). Heritability of adult body height: a comparative study of twin cohorts in eight countries. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 6(5), 399-408. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.6.5.399

- Visscher, P. M., McEvoy, B., & Yang, J. (2010). From Galton to GWAS: quantitative genetics of human height. Genetics Research, 92(5-6), 371-379. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672310000571

- Yengo, L., Vedantam, S., Marouli, E., Sidorenko, J., Bartell, E., Sakaue, S., … & Lee, J. Y. (2022). A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature, 610(7933), 704-712. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05275-y (open access)

- Activity: Summarize an Empirical Source

- Activity: Course Project Topic & Five Scholarly Sources

Week 5. Ancestry: What It Is and Isn’t

- Lecture: Monday

- Discussion: Wednesday

- Review Session: Friday

- Lecture Notes

- Population Genetics

- Scientific Racism

- Bird, K. A., & Carlson, J. (2024). Typological thinking in human genomics research contributes to the production and prominence of scientific racism. Frontiers in Genetics, 15, 1345631. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2024.1345631

- Dauda, B., Molina, S. J., Allen, D. S., Fuentes, A., Ghosh, N., Mauro, M., … & Lewis, A. C. (2023). Ancestry: How researchers use it and what they mean by it. Frontiers in Genetics, 14, 1044555. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1044555

- Martin, A. R., Kanai, M., Kamatani, Y., Okada, Y., Neale, B. M., & Daly, M. J. (2019). Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nature Genetics, 51(4), 584-591. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0379-x

- McLean, S. A. (2020). Social constructions, historical grounds. Practicing Anthropology, 42(3), 40-44. https://doi.org/10.17730/0888-4552.42.3.32

- Activity: Summarize a Review Source

- Activity: Plot Ancestry Principle Components in R

Part II: Phenotypes and Processes

Week 6. Schizophrenia: Psychometrics + Biometrics

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday

- Open Work Session: Friday

- Baker, C. (2004). Chapter Five: How Do Mental Disorders Emerge? pp. 59-72. open access book

- Hilker, R., Helenius, D., Fagerlund, B., Skytthe, A., Christensen, K., Werge, T. M., … & Glenthøj, B. (2018). Heritability of schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum based on the nationwide Danish twin register. Biological Psychiatry, 83(6), 492-498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.017

- Kendler, K. S. (2015). A joint history of the nature of genetic variation and the nature of schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry, 20(1), 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.94

- Sullivan, P. F., Yao, S., & Hjerling-Leffler, J. (2024). Schizophrenia genomics: genetic complexity and functional insights. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 25(9), 611-624. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-024-00837-7

- Trubetskoy, V., Pardiñas, A. F., Qi, T., Panagiotaropoulou, G., Awasthi, S., Bigdeli, T. B., … & Lazzeroni, L. C. (2022). Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature, 604(7906), 502-508. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04434-5

- Activity: Summarize a Scholarly Source

- Activity: Evaluate a Popular Source

Week 7. Autism: Heterogeneity and Disability Perspectives

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday

- Open Work Session: Friday

- Bai, D., Yip, B. H. K., Windham, G. C., Sourander, A., Francis, R., Yoffe, R., … & Sandin, S. (2019). Association of genetic and environmental factors with autism in a 5-country cohort. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(10), 1035-1043. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1411 (open access)

- Grove, J., Ripke, S., Als, T. D., Mattheisen, M., Walters, R. K., Won, H., … & Børglum, A. D. (2019). Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nature Genetics, 51(3), 431-444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8

- Koi, P. (2021). Genetics on the neurodiversity spectrum: Genetic, phenotypic and endophenotypic continua in autism and ADHD. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 89, 52-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2021.07.006 (open access)

- Natri, H. M., Chapman, C. R., Heraty, S., Dwyer, P., Walker, N., Kapp, S. K., … & Doherty, M. (2023). Ethical challenges in autism genomics: Recommendations for researchers. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 66(9), 104810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2023.104810

- Activity: Summarize a Scholarly Source

- Activity: Evaluate a Popular Source

Week 8. Causal Reasoning in Substance Use and Aggression

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday

- Lecture Notes

- Open Work Session: Friday

- Baker, C. (2004). Chapter Six: How Is The Ability To Control Impulses Affected By Genes And Environments? pp. 75-95. open access book

- Briley, D. A., Livengood, J., & Derringer, J. (2018). Behaviour genetic frameworks of causal reasoning for personality psychology. European Journal of Personality, 32(3), 202-220. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2153

- This piece gives an overview of methods of applying genetically informative data to causal reasoning. Although it’s about “personality,” that’s really only because it was written for a personality journal; you could swap the phenotypes and environments illustrated in Figures 1-3 and all the same reasoning would apply. The one element that is relatively specific to personality is the discussion of dominance (non-additive) genetic effects, which are not observed nearly as often for non-personality phenotypes.

- Karlsson Linnér, R., Mallard, T. T., Barr, P. B., Sanchez-Roige, S., Madole, J. W., Driver, M. N., … & Dick, D. M. (2021). Multivariate analysis of 1.5 million people identifies genetic associations with traits related to self-regulation and addiction. Nature Neuroscience, 24(10), 1367-1376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00908-3

- Treur, J. L., Munafò, M. R., Logtenberg, E., Wiers, R. W., & Verweij, K. J. (2021). Using Mendelian randomization analysis to better understand the relationship between mental health and substance use: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 51(10), 1593-1624. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172100180X

- Burt, S. A., Clark, D. A., Gershoff, E. T., Klump, K. L., & Hyde, L. W. (2021). Twin differences in harsh parenting predict youth’s antisocial behavior. Psychological Science, 32(3), 395-409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620968532

- Activity: Evaluate a Causal Claim

- COURSE PROJECT: Ten Scholarly Source Summaries

Week 9. Internalizing, Stress, and Gene-Environment Interaction

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday

- Open Work Session: Friday

- Grillo, A. R. (2025). Polygene by environment interactions predicting depressive outcomes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 198(1), e33000. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.33000 (open access)

- Hicks, B. M., DiRago, A. C., Iacono, W. G., & McGue, M. (2009). Gene–environment interplay in internalizing disorders: consistent findings across six environmental risk factors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(10), 1309-1317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02100.x

- Kendler, K. S. (2020). A prehistory of the diathesis-stress model: predisposing and exciting causes of insanity in the 19th century. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(7), 576-588. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19111213

- Levey, D. F., Stein, M. B., Wendt, F. R., Pathak, G. A., Zhou, H., Aslan, M., … & Gelernter, J. (2021). Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in> 1.2 million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nature Neuroscience, 24(7), 954-963. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00860-2

- Activity: Contextualize a Popular Source

Week 10. Cognitive Ability, Educational Attainment, and Gene-Environment Correlation

- Lectures: Monday, Wednesday

- Review Session: Friday

- Baker, C. (2004). Chapter Seven: How Is Intellect Molded By Genes And Environments? pp. 97-117. open access book

- Benning, J. W., Carlson, J., Smith, O. S., Shaw, R. G., & Harpak, A. (2024). Confounding Fuels Misinterpretation in Human Genetics. bioRxiv, 2023-11. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.01.565061 (open access)

- Chen, T. T., Kim, J., Lam, M., Chuang, Y. F., Chiu, Y. L., Lin, S. C., … & Won, H. H. (2024). Shared genetic architectures of educational attainment in East Asian and European populations. Nature Human Behaviour, 8(3), 562-575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01781-9 (open access)

- Haworth, C. M., Wright, M. J., Luciano, M., Martin, N. G., de Geus, E. J., van Beijsterveldt, C. E., … & Plomin, R. (2010). The heritability of general cognitive ability increases linearly from childhood to young adulthood. Molecular psychiatry, 15(11), 1112-1120. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2009.55

- Rimfeld, K., Malanchini, M., Packer, A. E., Gidziela, A., Allegrini, A. G., Ayorech, Z., … & Plomin, R. (2021). The winding roads to adulthood: a twin study. JCPP Advances, 1(4), e12053. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12053 (open access)

- Activity: Contextualize a Popular Source

Part III: Applications and Ethics

Week 11. Science Communication

- Lecture: Monday

- Discussion: Wednesday

- Open Work Session: Friday

- Lecture Notes

- Chapman, R., Likhanov, M., Selita, F., Zakharov, I., Smith-Woolley, E., & Kovas, Y. (2019). New literacy challenge for the twenty-first century: genetic knowledge is poor even among well educated. Journal of Community Genetics, 10, 73-84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-018-0363-7 (open access)

- Morosoli, J. J., Colodro-Conde, L., Barlow, F. K., & Medland, S. E. (2024). Scientific clickbait: Examining media coverage and readability in genome-wide association research. Plos one, 19(1), e0296323. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296323 (open access)

- Panofsky, A., Dasgupta, K., Iturriaga, N., & Koch, B. (2024). Confronting the “Weaponization” of Genetics by Racists Online and Elsewhere. Hastings Center Report, 54, S14-S21. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.4925 (open access)

- Reydon, T. A., Kampourakis, K., & Patrinos, G. P. (2012). Genetics, genomics and society: the responsibilities of scientists for science communication and education. Personalized Medicine, 9(6), 633-643. https://doi.org/10.2217/pme.12.69

- Roberts, J., Archer, L., DeWitt, J., & Middleton, A. (2019). Popular culture and genetics; friend, foe or something more complex? European Journal of Medical Genetics, 62(5), 368-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.12.005 (open access)

- Activity: Reflect on the open peer review materials provided with the Chen et al. (2024) paper from last week (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01781-9; the link to the Peer Review File is toward the bottom in the Supplementary Information section)

- COURSE PROJECT: Draft Paper

Week 12. Data Privacy, Law Enforcement, and Discrimination

- Lecture: Monday

- No Class: Wednesday, Friday

- Granja, R., & Machado, H. (2020). Forensic DNA phenotyping and its politics of legitimation and contestation: Views of forensic geneticists in Europe. Social Studies of Science, 0306312720945033. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312720945033 (open access)

- Katsanis, S. H. (2020). Pedigrees and perpetrators: uses of DNA and genealogy in forensic investigations. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 21, 535-564. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-111819-084213 (open access)

- Sabatello, M., & Appelbaum, P. S. (2017). Behavioral genetics in criminal and civil courts. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25(6), 289-301. https://doi.org/10.1097%2FHRP.0000000000000141

- Seaver, L. H., Khushf, G., King, N. M., Matalon, D. R., Sanghavi, K., Vatta, M., … & Ethical and Legal Issues Committee. (2022). Points to consider to avoid unfair discrimination and the misuse of genetic information: A statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genetics in Medicine, 24(3), 512-520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2021.11.002 (open access)

- Tzortzatou‐Nanopoulou, O., Akyüz, K., Goisauf, M., Kozera, Ł., Mežinska, S., Th. Mayrhofer, M., … & Makri, M. (2023). Ethical, legal, and social implications in research biobanking: A checklist for navigating complexity. Developing World Bioethics. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12411 (open access)

- Activity: Write an Imaginary Press Release

- COURSE PROJECT: Draft Popular Source

Week 13. Genetic Engineering

- Lecture: Monday

- Discussion: Wednesday

- No Class: Friday

- Lecture Notes

- Doudna, J. A. (2020). The promise and challenge of therapeutic genome editing. Nature, 578(7794), 229-236. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1978-5

- Grebe, T. A., Khushf, G., Greally, J. M., Turley, P., Foyouzi, N., Rabin-Havt, S., … & Social, A. C. M. G. (2024). Clinical utility of polygenic risk scores for embryo selection: A points to consider statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genetics in Medicine, 26(4), 101052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2023.101052

- Gyngell, C., Bowman-Smart, H., & Savulescu, J. (2019). Moral reasons to edit the human genome: picking up from the Nuffield report. Journal of Medical Ethics, 45(8), 514-523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-105084 (open access)

- Activity: Identify Themes in a Popular Source

- Activity: Popular Source Peer Reviews

- COURSE PROJECT: Paper Peer Reviews

Week 14. Personalized Medicine, Personalized Education, and Direct-To-Consumer Tests

- Lecture: Monday

- Discussion: Wednesday

- Open Work Session: Friday

- Eeltink, E., Van der Horst, M. Z., Zinkstok, J. R., Aalfs, C. M., & Luykx, J. J. (2021). Polygenic risk scores for genetic counseling in psychiatry: Lessons learned from other fields of medicine. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 121, 119-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.021 (open access)

- Gómez-Carrillo, A., Paquin, V., Dumas, G., & Kirmayer, L. J. (2023). Restoring the missing person to personalized medicine and precision psychiatry. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1041433. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1041433 (open access)

- Martschenko, D. (2020). DNA dreams: Teacher perspectives on the role and relevance of genetics for education. Research in Education, 107(1), 33-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523719869956

- Majumder, M. A., Guerrini, C. J., & McGuire, A. L. (2021). Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: value and risk. Annual Review of Medicine, 72, 151-166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-070119-114727 (open access)

- Rubanovich, C. K., Taitingfong, R., Triplett, C., Libiger, O., Schork, N. J., Wagner, J. K., & Bloss, C. S. (2021). Impacts of personal DNA ancestry testing. Journal of Community Genetics, 12, 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-020-00481-5

- Activity: Identify Themes in a Popular Source

- COURSE PROJECT: Final Popular Source

Week 15. GATTACA, and Genetics as a Social Construct

- Movie Showing & 20 Themes BINGO: Monday, Wednesday

- Lecture Notes

- Ogbunugafor, C. B., & Edge, M. D. (2022). Gattaca as a lens on contemporary genetics: marking 25 years into the film’s “not-too-distant” future. Genetics, 222(4), iyac142. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/iyac142 (open access)

- So, D., Crocker, K., Sladek, R., & Joly, Y. (2022). Science fiction authors’ perspectives on human genetic engineering. Medical Humanities, 48(3), 285-297. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2020-012041

- Activity: Genetics in Fiction

- Activity: Design Your Own Gene

- Activity: Five Big Ideas

Finals Week

- COURSE PROJECT: Final Paper due by 5 pm on what would have been our “Finals Day” (TBD)